For Sale: Birectifier Beverage Distillate Analysis Kit ($900USD)

A unique mid century document came to me a few years ago containing the intimate but anonymous production parameters of 42 American whiskey distilleries producing 112 different whiskey mashes (85 Bourbons, 10 rye mashes, and 17 corn mashes). To my knowledge, the document is not known to any spirits scholars.

My plan to explore the document started with a scheme to unmask all the distilleries by tricking the conglomerates into matching their famous straight Bourbon labels to the old productions. I appealed for help, but didn’t get any interest, so it seemed like time to explore it another way. It was also complicated by the fact that these were just mashes and not labels themselves. Straight Bourbons could be picked out, but blends would be very complicated if not possible anymore.

Many brands making come backs have devolved into merely labels detached from the juice that was inside. As we will see when compared, many of the mashes were fairly redundant, featuring only slight variations. Brilliant progressive thinkers like Herman Willkie and Paul Kolachov were making production much more efficient in the name of environmental burden while also producing a great product. Their quest for genuine improvement was a big factor in the consolidation trend.

Distillery tourism is the new trend that may reverse the label detachment phenomenon and producers may be interested in de-consolidating their products back to more uniqueness so we have more places to visit, collect, and obsess over. The market for fine products and tourism make a lot of things newly viable, what we need then is a vision for style.

New players are entering the market that are financed well enough to be the truth seekers we need such as Kevin Plank’s Sagamore spirits. Sadly, they are starting with MGP, but they have picked up Seagram’s alum, Larry Ebersold. No doubt the parameters of gems like the legendary Baltimore Pure rye lie in the document. It shouldn’t be hard to spot the rye-est of all the ryes. Distillery no. 3, a conglomerate, made some brick house ryes, but distillery no. 38 made nothing but rye with one mash being a pure rye malt monster and their other mash being more economy oriented.

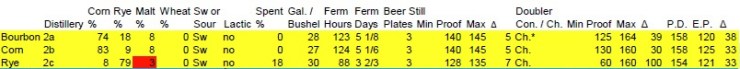

To contextualize the document, I have reorganized it into a spread sheet that makes trends and patterns more obvious. Hopefully some historians that have studied company timelines and have knowledge of the producer’s various labels can chime in and we can start giving probabilities of who is who. There are only two different wheaters and one corn producer using koji so it won’t be too hard to name the obvious.

The document gets specific and tells us the unique production parameters used by each distillery. Many only made Bourbon while others added a corn whiskey or rye and a few made all three. If they added that corn mash, they likely had a proliferation of labels for blends. Some mash bills were reused with different parameters and the spreadsheet lets us see that all comparatively. Most whiskey back then was commodity whiskey as opposed to the new fine market we see now and the document shows producers varying production parameters to make different crus, at least as blending stock, under one roof. This wasn’t the single barrel era yet. Who knows how they allocated production slots when they had multiple mashes in their repertoire. Some mashes were obviously modest while others were grander and some with a grand foundation were distilled to be a little lighter on their feet as supposedly was the trend.

The document was commissioned because fusel oil separation in continuous stills, the so called extractive distillation, was changing whiskey identity markedly. Only six of the forty two distilleries exclusively used batch distillation. Laws limiting distillation proof to imply character are all based on the assumption of batch distillation. A continuous still can be tuned so that various side streams strip out the heavy character of fusel oil. Producers, no doubt led by Willkie and Kolachov, were also moving to advance fermentations, biological control, to alter much of a whiskey’s character pre distillation and aging (following the lead of rum!). The document was an attempt to mark a golden era of American whiskey before it went too wayward beyond “tradition”. Keep in mind, I may also be over dramatizing things.

For each itemized production, we have their:

•Mash bills, percent corn, rye, wheat, and malt

•Whether it was a sweet or sour mash

•Whether a lactic culture was added

•The percent of backset or stillage used to sour the mash

•The gallons per bushel of grain which implies alcohol concentration for the mash

•Duration of fermentation in hours

•I computed duration in days so we can think in terms of labor shift changes

•Plates on the beer still

•Min and max proof of the stripping run

•I compute the difference to imply how the still is refluxed to come to a relative equilibrium before the run is collected.

•Whether the doubler is a batch charge or continuous.

•Min and max proof of the doubling run

•I again compute the different to extrapolate a little more

•Proof of the final collected distillation

•Entry proof into the barrel.

•I compute the difference because the grandest products will require the least dilution, just like a rum.

Corn is cheaper than other grains and too much corn in a mash bill can leave a rank taste at lower drinking proofs if distilled very low. It tends to be served above 80 proof to contain the flavor. In the era of the document, corn whiskey was still a thing, if not just for blending. Three distilleries exclusively made corn whiskey. One was still using the infamous ultra efficient and therefore cheap koji process developed by Dr. Jokici Takamine in the late 19th century. This is likely a Peoria Illinois producer, but possibly not Hiram Walker. Distillery no. 1 is likely the most heritage of all the corns. They still used batch distillation, though with a few plates, and no refluxing of the stills before they collected the run. Bourbons very high on the corn make me think of bottlings like Dant that I’ve tasted from the 1970’s that kind of sucked.

Higher rye content Bourbons, like Old Grand Dad, start to mark quality. Some whiskeys like example no. 3c were probably quite tasty. Distillery 3 was one of a few big conglomerates and it is interesting to compare their bourbons. Whiskeys 3a and 3b are subtle variations of each other and do not read as grand as 3c in terms of rye content, yet their fermentation times are slightly longer. Were any of these new acquisitions that were likely to be redundant and consolidated?

Speaking of conglomerates, distillery no. 3 is the most apparent, but the similarity of parameters in distilleries no. 5,6, and 7 make it seem like they were all under the direction of a single team. Could that be where Willkie and Kolachov come in?

Only two distilleries made Wheat mashes, and they loved their concept enough to make nothing but. One is Stitzel-Weller and the other is likely Maker’s Mark. Language in the document’s commentary implies that the wheaters are two distinct enterprises. Both distilleries used the same mash bill, the same single plate stripping still concept, similar lack of refluxing, and even the same barrel entry proof. Bill Samuels was known to acquire his recipe and receive assistance from Stitzel-Weller and the data could add conjecture to the extent of the help. My guess is that the more contemporary Maker’s Mark is the wheater that distills at the higher proof.

Malt is an interesting variable in a mash bill and it is thought only to provide assistance for converting starch to fermentable sugars, but it may also be stylistic judging by the varying proportions of its use. Malt is expensive and if a producer went heavy on it, they likely had a good reason. The highest malt content on the board is the 20% from whiskey no. 38b. That was from the rye exclusive producer and was matched with 80% rye which leads me to believe it was the Baltimore Pure Rye. I had been lucky enough to taste a bottle of BPR 1941 and it had a unique and dense maltiness very unlike any Old Overholt I had tasted of the same era. Overholt could possibly be derived in part from the ryes of distillery no. 3. which may be National Distillers (just a guess!).

Malted barley has a much higher diastic power than malted rye so when the malt figure is at the average, it is likely the more economical barley, but if it is as high as 20, it is probably decadently rye. Northern Brewer has started selling different malt extracts and their rye is quite singular. What would be cool to know is if there was a style of Bourbon mash that seemed like it was high on the corn, but was rye plus rye malt (instead of barley) so it really tasted distinctly high rye.

Few producers still made a sweet mash with two producers doing it exclusively. The rule of thumb with sweet mashes is that they can ferment faster and to higher alcohol contents than a sour mash. Distillery no. 2 made a sweet Bourbon mash, corn mash, and rye. Their rye is categorized as sweet but still employed 18% backset. Distillery no. 42 followed suit with two categorized sweet but also featuring 20% backset. The traditional quantity of backset for sour mash is 25% so anything less than that is considered sweet by the industry. Notice the first part of the rule of thumb falls part and distillery no. 2 happens to use decadently long fermentations though the second part holds true and they use a low gallons of water per bushel. Style points for no. 2! [that red three I think is their typo and should be a 13]

The addition of a lactic acid producing bacteria was something that surprised me when I first read the document. Co-fermentation of yeast with an innoculated bacterial culture is something that we think of in rum production, but here it was, thoroughly used in American whiskey and practiced for decades. I have yet to find an old research paper that focuses on it.

When you really get into it, the way they add their lactic culture is also very different than rum. Rum bacteria is all offense and aroma driven while sour mash’s lactic culture is all defense. Many inferior wild yeasts and aroma negative bacteria can not grow in the low pH medium produced by the lactic bacteria. Sour mash yeasts are unique and they used to be called wine-sour yeasts because they were selected for tolerance to soured mashes.

Innoculating with a lactic culture may seem high tech like sour mashers graduated from mere chemical control to full on biological control, to borrow rum industry phrasing, but they were practicing it since before the 19-teens. They made it like yogurt. A small amount of a rye and malt specialty mash is held at about 120°. This temperature is beyond a yeast’s tolerance, but the lactic bacteria can grow and take hold. It wasn’t too fussy.

The bacteria basically infects the vat and accumulates in every batch to a point where fermentation is impeded and the vats must be chemically sanitized. These days under near complete biological control, some producers have advanced to the point where they have inline spectroscopy monitoring the beer telling them specifically if they need to clean the vats on the 18th, 19th, or 20th batch in the cycle. Too soon would be wasteful.

The sweet mash producers obviously did not add a lactic culture, but twelve sour mash producers also did not use it in any of their productions. These producers likely have a healthy variation of character during their production cycles and they tended to have smaller lineups such as one mash bill with variations of fermentation duration. I imagine Old Crow lying in this Bourbon philosophical territory somewhere. Its reputation was beyond the state of its production so the label was kept, but its mash bill was consolidated.

Gallons of water per bushel tells us how dilute the beer was and what its potential alcohol was. It also somewhat tells us how grand the aspirations of the ferment were. More water meant a larger mass to absorb the heat of fermentation which would keep the temperature down creating less aroma negative congeners that in the olden days would be a concern for batch distillation. More water also means more capital tied up storing the extra mass of the beer and far more energy used to boil it all in the end; so if you added it, the results had to justify it. Just like rum, progressive producers were migrating to temperature controlled fermentation vats and higher starting gravity fermentations to use less fuel.

There used to be legal guidelines governing gallons per bushel (to promote hitting dryness) and even a provision for rum, but who knows where those ideas were by the time the document was commissioned. This relates to the idea of chemical control of a distillery. If you go way back, American excise officers used to actually help distilleries become scientifically competent. We just didn’t know enough about fermentation is those days and without care it was easy to get a fermentation stuck and squander potential alcohol before you distilled. The excise job would be phenomenally easier if all producers were guaranteed to ferment to dryness. The producer would also make more money and have less incentive to cheat.

When fermentation competence is the rule, the reason the excise job gets easier is because you can match potential alcohol from grain purchased to alcohol realized from the still. There will be losses but extrapolations can account for them. The excise officer becomes a stable pencil pusher and not a nosy detective with a flashlight only to find the distiller is incompetent. The scope of the IRS papers that keep turning up surprise a lot of people, but hopefully this explains their philosophy. Many of the excise guys no doubt loved whiskey. The bulletins they put out gave them a proper forum to influence the industry instead of being an annoying backseat driver on the distillery floor.

Longer fermentation times typically correlate to fuller flavored beers to distill (and there also used to be legal minimums aimed at helping hit dryness). This lesson is best learned in rum where there is a bigger spread in possibilities. In the document, we see fermentations as short as 52 hours for a corn mash and as long as 120 hours for quite a few others whiskeys.

One thing I did in the spread sheet was to convert the hours to days to look at the durations in terms of human labor cycles. Fermentation times weren’t exactly just carried out until specific congener targets were met, besides the obvious completion of converting sugar to alcohol. They were carried out until someone showed up to do the work of manning the pumps. If we look at distillery no. 27, an infamous wheater producing three variations of the same mash bill, they had a 72 hour fermentation, an 84, and a 96. In terms of days that is 3, 3½, and 4. So the question is, did they start with the objective of producing different styles or did it just happen when a runaway biological process met the rhythm of their labor cycles? Distilleries don’t employ a lot of people and that 84 hour ferment may have happened because he/she simply didn’t get to it yet. New distilleries are starting to encounter human rhythms dictating production practices while large distilleries have overcome aspects of it with automation.

Bourbon got pretty far without being too fussy about bio technology. Excise officers helped them out and the sour mash process took form without much more science than it took to make yogurt. They also grew and maintained fairly pure strains of wine-sour yeasts without owning microscopes. That was done using hops. Rum didn’t have hops to keep bacteria from their yeast and that is why Arroyo had to be such a thorough bio technologist (rum eventually used antibiotics).

I’ve actually never looked into the specifics of Bourbon producing stills. I thought that maybe they flirted with fully continuous distillation and reverted back based on pictures I’d seen, but that isn’t exactly the case. The document differentiates between variables in the beer still versus what they label the doubler so it looks like the beer still is a discontinuous charge process while the second distillation is continuous. Multiple beer stills could feed a continuous doubler (but confirming that is still a google away). I could be wrong, I haven’t actually looked.

If a distillery operated a continuous beer still, and they definitely existed capable of digesting grain left in the mash, it would have between 12 and 20 plates. If a still had that many plates, they also likely wouldn’t need a second distillation. The most plates for a beer still in the document is 10 which is distillery no. 24 who exclusively made Bourbon. Mash no. 24b has a significant spread between the minimum and maximum proof so it is likely not continuous. Laws I’m not aware of may have dictated a double distillation scheme.

The plates, disclosed in the document, will somewhat correlate to the flavor passed on to the doubler, but not as much as the minimum and maximum proof of the beer run. Only three distilleries use a different amount of plates across their productions which could imply different entire stills in use or possibly just different columns switched on or off. Both wheaters use a one plate still which could imply a little more collusion.

I computed the difference between the minimum and maximum proof of the beer still run. The idea was so see if they refluxed the stills to bring them to relative equilibrium before collecting the run. A pot still is not at equilibrium and the run has a significant curve when you graph the proof over time so you see a big difference between minimum and maximum. A column still can be operated at relative states of equilibrium flattening out the curve. Collection from a column still can be paused by going full reflux, but the alcohol content in the column will increase. The ability to reflux means that multiple beer stills could be synced up with a continuous doubler even if they didn’t exactly heat at the same rate.

It would be so cool to see the same data from ten years prior. I suspect the industry was much more susceptible to trends over tradition. They all no doubt read the same research papers and bulletins especially with excise officers ever present and ever helpful. They likely also had consultants and I doubt anyone was too guarded which is how Maker’s Mark could emerge out of Stitzel-Weller without a scandal. I say that all by looking at the data and the industry research papers I’ve read that may have influenced the numbers. I don’t actually know any specific industry anecdotes. I have never particularly paid attention to American whiskey before so there is lots of room to add to or tear apart all my ideas here.

Continuous doublers must have been around for quite a while if so many people had them. There was probably a generation of equipment used right out the gates of prohibition that lasted maybe twenty years then everybody upgrading at the same time possibly as they exited the pressures of World War II.

You would think continuous stills would all be operated very similarly with very tight spreads between the minimum and maximum proof of distillation and quite a few producers had really tight spreads. Yet there is also a lot of variation such as distillery no. 14 distilling handsome seeming Bourbon mashes, but having a significant spread of 42 proof on their doubler relative to only 10 on their 2 plate beer still. Those numbers are very different than distilleries no. 5,6 and 7, which may all be the same conglomerate. The spread on 5,6, and 7 is as tight as the probable margin of error. Distillery no. 9 supposedly starts collecting from their continuous doubler at zero proof which may be possible if they are collecting steam and not allowing the column to come to any state of relative equilibrium before they collect their distillate (excise officer is rolling his eyes). There are some gaps in the data where distilleries did not answer the questions denoted by a “-“. It is hard to say if that zero should be taken at face value, if its an error, or if someone did not understand the question. The questionnaires were actually filled out by excise agents. Distillery no. 2 also operated their continuous doubler with unusually wide spreads. The wheater, no. 16, also did, but I am not confident in those numbers because they are exactly the same as used in their beer still while the second wheater’s, no. 27, are not.

Final distillation proofs and then barrel entry proofs are hard to read into. Classically, economy whiskeys and just plain junk were distilled at higher proofs to make them more palateable. Grander whiskey would be distilled lower, but then there was the trend to lighter on their feet whiskeys. At the same time, and the whole point of the document, was that producers were slowly learning to use their continuous doublers with the ability to easily separate fusel oil and changing American whiskey identity markedly. I bet there was even one infamous Bourbon that set the precedent while everyone watched in amazement (Yellowstone). I would not be surprised if Kolachov had anything to do with it and it shouldn’t be hard to figure out what whiskeys had his name on them. All of the rules of thumb were falling apart. A new era of whiskey abstraction was dawning.

What I’ve barely mentioned so far is that all the data came with a commentary, but they don’t explain or explore pretty much any of the stuff I just presented. Their vantage point was much different. There is also lots of data I’m not showing because it is a bunch of boring congener counts. That data is boring but powerful. Columns could be added to the spread sheet with all the major congeners classes. We could then use econometrics and software like SPSS to find correlations. This would possibly generate statistically significant actionable advice such as increase the fermentation time if you want to increase the X and decrease the Y. We can leave that all for another day.

The authors were concerned with the potential of extractive distillation which is a method of fusel oil separation. Laws stating that distillation could not exceed 160 proof was not guaranteeing anything anymore. They were positing writing into law natural flavor standards for each congener class. The impact of extractive distillation may not have hit whisky yet, but the future comes at you fast. If natural flavor standards had to be created, they needed good numbers representative of tradition while they still were reliable.

The authors also explained a few bits and pieces in the data. The two curious “water-mashes” with no backslopping could make a whiskey lighter because less congeners are recycled by the backslop. They were also using early forms of GCMS and connecting chemical compounds to the infamous hog tracks of some new make spirits

The authors note that the maximum allowable entry proof was raised in 1962 from 110° to 125° yet average entry proof for Bourbon’s was still 109.8°. None of the bourbons were entered at the maximum allowable proof. That makes it hard to understand why the laws bother to change. The commentary section of the document has a table that compares various similar surveys conducted between 1898 and themselves. I have seen a lot of them and none are as comprehensive or have such an extensive table of mashing and distilling parameters.

It has often been stated that whiskies produced today are not as heavy or full bodied as those produced in the old days. To find evidence that would either support or refute this contention, a comparative examination of chemical data from the better known studies on whisky has been made and is shown in Table 7.

The data leads to the conclusion that not much has changed.

Possibly the heavier charring of the barrels resulted in the so-called “heavy whiskies” of the old days.”

It was a lot of fun to reflect upon and finally do something with this cool document. Hopefully it will launch a few ships, start a few friendships and generate new chapters of American whiskey writing and scholarship.

Notes:

Wild Turkey was an non distiller bottler until the 1970’s and started as a supermarket brand.

Distillery no. 41 is likely Continental Distilling of Pennsylvania based on the 41C mash bill of 37/51/12 which is likely Rittenhouse Rye

Heaven Hill has used a 75/13/12 mash bill so they could be distillery no. 10,15, 18, 21 ,23, 24c, 25, or 30. Basically it is the most popular mash bill. Wild Turkey eventually became a 75/13/12 so they could be descended from one of these producers.

Distilleries 16 and 27 are likely Stitzel-Weller and Maker’s Mark.

Distillery 24 could be Four Roses because they do two different mash bills. Currently one with 75% corn, 20% rye, and 5% malted barley and another one with 60%, 35% rye, and 5% malted barley. The rye percentages could have changed from the days of the document as ideas in malt changed. Four Roses uses five different yeasts! Holy Biological control Batman!

Distillery 19 is likely George Dickel. Their current mash bill is disclosed as 84% corn, 8% rye and 8% malted barely which doesn’t match anybody. The document would consider them a corn mash producer and the only producer of quality doing exclusively corn mashes is no. 19. Dickel was a contemporary plant back then so it is probably not distiller no. 1.

Distiller no. 7 could be the Barton distillery because of the 75/15/10 mash bill that they claim to use today, but don’t forget they may some how be linked to distillery no. 6 because parameters over lap.

Today Maker’s Mark discloses uses the same mash bill as in the document.

Distillery no. 9 is likely Jack Daniels because of the 80/8/12 mash bill. Others used the same mash bill, but no. 9 was the only one that produced exclusively that. I’ll have to check the chemical data and see if there is anything odd that makes it look like its definitely charcoal filtered.

Distillery no. 17 is likely Brown Forman because of the 72/18/10 mash bill, but it looks like that distillery also ran a 74/16/10.

If distillery no. 3 is National Distillers, bourbon 3c could be Old Grand-dad, 65/25/10. These days the Grand-Dad mash bill is disclosed as 63/27/10.

Distillery no. 3 is likely Hiram Walker based on a paper about aging I’ve got where they used samples from three distilleries with proofs of distillation 154 for a rye, 118, and 127 for Bourbons.

If Michters at Bomberger’s distillery was always a pot still distillery, they could likely be distillery no. 41. but at the beginning I thought that was Rittenhouse. Which could mean they are definitely Pennsylvania Rye numbers.

Perfecto.

Do you think lactic acid bacteria were added as a biological control or for flavour purposes? Esterification of lactic acid with various alcohols produces flavours often associated with Scotch. Many Scotch producers have indigenous bacteria within the distillery.

Definitely both!

http://www.microbiologyresearch.org/docserver/fulltext/micro/147/4/1471007a.pdf?expires=1533211742&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=94C6917EA9FCDD33EC0486205E52CB4A

Reading things like this, do you know of any attempts by bourbon producers to cultivate idiosyncratic LAB? Seems like it would be of interest but I haven’t read of anyone trying it.

I know there are some in the World Distilled Spirits Conference compendiums. I remember one year where yeast and bacteria were a focus. I haven’t tracked them down in a few years, but I remember finding PDFs of them online.

Is this document available to read anywhere? I am curious about a lot of things, particularly the comparison to previous 1898 surveys.