Follow along: IG @birectifier

[I am going to update this a little bit to note what from the presentation my team (Cory and I) has since brought to life.]

I just recently presented at Lallemand’s incredible Alcohol School in Kingston, Jamaica. This post is my reformatted presentation as a blog post. Consider it skimmable. My aim was to present Grand Arôme / High Ether rums as a powerful tool to drive agrotourism, but that was a bit lost on the very technical audience. Many really enjoyed the nuts and bolts look at these rums and quite a few people in the audience actually produce them as their day to day. Below each slide will be my speaker notes.

After the presentation one of the interesting conversations I had was on the different language I used throughout. My thoughts are that we need three sets of language. One for marketing to consumers, one for talking scientist to scientist, and a third for talking to investors. You definitely need a vocabulary for each.

My presentation came a day after a very exciting presentation from Vivian Wisdom about producing high ether rums at Hampden. Vivian represented a very practical perspective of someone who actually makes these rums while I only represent literature which was all lost until recently. I’ll write more in another post, but what was revealed is that Vivian’s rums likely use a Pombe yeast (based on osmotic pressure he describes), and he certainly know how to harness it, but his generation has lost the ability to differentiate it from Saccharomyces. That may be why we don’t hear about it. Another issue was that no one in the room uses the term rum oil. The ability to differentiate it from fusel oil has been lost (overlapping volatility). The Appleton’s foreman was aware of the rum oil concept, but he was also the kind of careful about speaking too freely. When I passed around isolated samples of rum oil from fraction 5 of the birectifier, the character was widely recognized by the room. However, no one seemed to be aware of its chemical precursors which I present strong theories for. One more issue is that there is a fermentation complication used in Jamaica that a few people admitted to losing track of the purpose and origins of. Something parallel is described in the literature (and my presentation) and I have some theories on the Jamaica method I’ll have to write up after I investigate a little more.

[Many producers have since admitted to using schizosaccharomyces yeasts but it has not yet been reflected in anyone’s marketing. No major producers have done anything with “rum oil”.

The Grand Arôme category represent the broadest traditions in rum. Their late 19th century origins were in excise and tariff pressure. They were re-imagined mid century by Rafael Arroyo and we are in a position to re-imagine them again. Today, I am going to present a new framework for doing so that revolves around the traditional yeast Schizosaccharomyces Pombe and the concept of fermentation complications.

The Grand Arôme category represent the broadest traditions in rum. Their late 19th century origins were in excise and tariff pressure. They were re-imagined mid century by Rafael Arroyo and we are in a position to re-imagine them again. Today, I am going to present a new framework for doing so that revolves around the traditional yeast Schizosaccharomyces Pombe and the concept of fermentation complications.

When we talk about the Grand Arôme tradition today, we talk about a collection of named traditions from around the world, but we let one term win because of its marketability to the present day rum consumer. At the time these names were coined and processes developed, these specific rums saw near no end consumer interaction and only existed to producers, commercial consumers, and scientists. This presentation presents the patterns that emerged after collecting and sifting through 150 years of technical rum literature.

When we talk about the Grand Arôme tradition today, we talk about a collection of named traditions from around the world, but we let one term win because of its marketability to the present day rum consumer. At the time these names were coined and processes developed, these specific rums saw near no end consumer interaction and only existed to producers, commercial consumers, and scientists. This presentation presents the patterns that emerged after collecting and sifting through 150 years of technical rum literature.

[Savanah, in Reunion island has been using Grand Arôme as a marketing tool, but it isn’t known if they produce a pombe rum.]

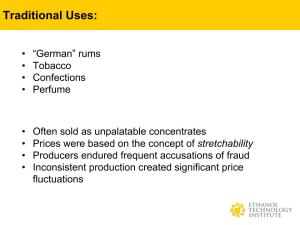

Tobacco use is best associated with Felton & Son’s of Boston and comes to us from congressional testimony related to Prohibition. Confection use is anecdotal regarding Batavia Arrack, but also exists in the literature regarding Japanese firms. Perfume use is best associated with Hampden estates DOK High Ether Rum in Jamaica as well as Martinique firms. Desiree Kervegant, writing in 1936, describes a decline in interest due to fears of fraud. H.H. Cousins who invented the High Ether Process in Jamaica also described persistent accusation of fraud and price volatility.

Tobacco use is best associated with Felton & Son’s of Boston and comes to us from congressional testimony related to Prohibition. Confection use is anecdotal regarding Batavia Arrack, but also exists in the literature regarding Japanese firms. Perfume use is best associated with Hampden estates DOK High Ether Rum in Jamaica as well as Martinique firms. Desiree Kervegant, writing in 1936, describes a decline in interest due to fears of fraud. H.H. Cousins who invented the High Ether Process in Jamaica also described persistent accusation of fraud and price volatility.

The sugar technologist and historian Hubert Von Olbrich gives us diagrams illustrating ester properties of various rums and here the blending proportions. Some commodity German blends had as little as 10% original rum which could provide identity due to the persistence and stretchability of high value congeners.

The sugar technologist and historian Hubert Von Olbrich gives us diagrams illustrating ester properties of various rums and here the blending proportions. Some commodity German blends had as little as 10% original rum which could provide identity due to the persistence and stretchability of high value congeners.

[We are producing Grand Arôme rums with startling stretchability from rum oil which can live up to these proportions.]

The Grand Arôme rums somewhat help us flip the rum narrative, confirming what many of us know, and promoting fermentation in our discourse above distillation which too often gets more attention. Spirits are always distilled at the peak potential of their fermentation so we know which should lead. Hopefully this can guide the marketing department as well as research and process investment. [Circular 106, Rum Manufacture, Rafael Arroyo, 1938]

The Grand Arôme rums somewhat help us flip the rum narrative, confirming what many of us know, and promoting fermentation in our discourse above distillation which too often gets more attention. Spirits are always distilled at the peak potential of their fermentation so we know which should lead. Hopefully this can guide the marketing department as well as research and process investment. [Circular 106, Rum Manufacture, Rafael Arroyo, 1938]

To guide us, I’m going to quote rum marketer Alexandre Vingtier. This helps us consider why we should expend the effort to make complicated and challenging rums.

To guide us, I’m going to quote rum marketer Alexandre Vingtier. This helps us consider why we should expend the effort to make complicated and challenging rums.

These sentiments guide the importance of rum and leading marques. Beautiful products intangibly act as ambassadors and very tangibly generate agro tourism whose potential is incredible. All advancement in the rum industry going forward would be wise to integrate themselves to agro tourism. If the most deeply guarded production practices are disclosed and philosophy explained, just like the wine industry, people will want to show up and see it. Tremendous value can only be unlocked by openness.

These sentiments guide the importance of rum and leading marques. Beautiful products intangibly act as ambassadors and very tangibly generate agro tourism whose potential is incredible. All advancement in the rum industry going forward would be wise to integrate themselves to agro tourism. If the most deeply guarded production practices are disclosed and philosophy explained, just like the wine industry, people will want to show up and see it. Tremendous value can only be unlocked by openness.

The French literature was where I first heard of the Grand Arôme rums. When I asked renowned INRA micro biologist, Louis Fahrasmane, about Grand Arôme rum I was given this caution. Not all of these rums declared themselves as such and some that do may not have deserved it. Little formal criteria was ever created. These rums were also handed off between producer and industrial consumer with little communication in between so few ever got a complete picture of their production and eventual use. [INRA bibliography and collection of translations]

The French literature was where I first heard of the Grand Arôme rums. When I asked renowned INRA micro biologist, Louis Fahrasmane, about Grand Arôme rum I was given this caution. Not all of these rums declared themselves as such and some that do may not have deserved it. Little formal criteria was ever created. These rums were also handed off between producer and industrial consumer with little communication in between so few ever got a complete picture of their production and eventual use. [INRA bibliography and collection of translations]

Grand Arôme rums typically employ Schizosaccharomyces Pombe as a yeast. In the 19th century when Jamaica rum and Batavia Arrack fetched the highest prices in the world for spirits, the commonality was Pombe. Pombe yeasts are associated with the pursuit of rum oil which is the most valuable congener in a spirit. Rum oil could be a called a High Value Terpene (HVT) which is the language of terpene scientists that aggressively pursue them for industry. Some fetch tens of thousands per kilogram and are often engineered in elaborate E. coli driven bio reactors. High Value Terpenes are at the center of various luxury consumption from Cannabis to perfume fixatives to cosmetics and shampoo, artificial sweeteners, and spices like Vanilla bean and Saffron. Long chain esters are a big focus of Grand Arôme rum production but are subordinate to rum oil. Together with other obscure compounds that share a band of low volatility we can group them as High Value Congeners (HVCs). Rum oil is often ignored because before spectroscopy it was hard to study since you can not titrate for terpenes. Historic data that can imply rum oil content is available as indexes of persistence.

Grand Arôme rums typically employ Schizosaccharomyces Pombe as a yeast. In the 19th century when Jamaica rum and Batavia Arrack fetched the highest prices in the world for spirits, the commonality was Pombe. Pombe yeasts are associated with the pursuit of rum oil which is the most valuable congener in a spirit. Rum oil could be a called a High Value Terpene (HVT) which is the language of terpene scientists that aggressively pursue them for industry. Some fetch tens of thousands per kilogram and are often engineered in elaborate E. coli driven bio reactors. High Value Terpenes are at the center of various luxury consumption from Cannabis to perfume fixatives to cosmetics and shampoo, artificial sweeteners, and spices like Vanilla bean and Saffron. Long chain esters are a big focus of Grand Arôme rum production but are subordinate to rum oil. Together with other obscure compounds that share a band of low volatility we can group them as High Value Congeners (HVCs). Rum oil is often ignored because before spectroscopy it was hard to study since you can not titrate for terpenes. Historic data that can imply rum oil content is available as indexes of persistence.

[Since we have learned that the modern perfume industry (worth startlingly more than the rum industry) is centered around the various high value terpenes that may constitute rum oil (rose ketones).]

Tremendous marketing potential exists in Grand Arôme rums. The complications term does not come from the rum literature but is borrowed from horology where it refers to features on a chronometer such as besides the time, telling the day of the month, the phase of the moon, etc. Grandness comes from juggling complications. Consumers pay top dollar for more than the utilitarian.

Tremendous marketing potential exists in Grand Arôme rums. The complications term does not come from the rum literature but is borrowed from horology where it refers to features on a chronometer such as besides the time, telling the day of the month, the phase of the moon, etc. Grandness comes from juggling complications. Consumers pay top dollar for more than the utilitarian.

Recently a luxury watchmaker included a capsule of the oldest known rum in a limited edition grand chronometer.

Recently a luxury watchmaker included a capsule of the oldest known rum in a limited edition grand chronometer.

An enduring word of caution from Charles Allen of the Jamaican Agricultural Experiment Station who taught an early course for distillers. Everything is easier said than done.

An enduring word of caution from Charles Allen of the Jamaican Agricultural Experiment Station who taught an early course for distillers. Everything is easier said than done.

Rum oil likely has two branches of precursors. The first being glycosides which was hypothesized early on and the second being carotenoids. In Australia in 1975, D.A. Allen analyzed the side stream of a continuous distillation production at Bundaberg. What Allen ends up isolating and attributing to rum oil is 1,1,6-trimethyl-1,2-dihydronaphthalene which is the carotenoid the wine industry calls TDN and is responsible for the petrol character in reisling wines. In one of the most startling papers on the topic of Jamaica rum and Batavia Arrack from 1936, the Anonymous author was already hypothesizing glycosides (Die Fabrikation des Jamaika – Rums und des Batavia – Arraks, Deutsche Destillateurs Zeitung, 1936). Recent Cognac literature also attributes Cognac oil to glycosides.

Rum oil likely has two branches of precursors. The first being glycosides which was hypothesized early on and the second being carotenoids. In Australia in 1975, D.A. Allen analyzed the side stream of a continuous distillation production at Bundaberg. What Allen ends up isolating and attributing to rum oil is 1,1,6-trimethyl-1,2-dihydronaphthalene which is the carotenoid the wine industry calls TDN and is responsible for the petrol character in reisling wines. In one of the most startling papers on the topic of Jamaica rum and Batavia Arrack from 1936, the Anonymous author was already hypothesizing glycosides (Die Fabrikation des Jamaika – Rums und des Batavia – Arraks, Deutsche Destillateurs Zeitung, 1936). Recent Cognac literature also attributes Cognac oil to glycosides.

[We since have a smoking gun from the French literature tying rum oil to rose ketones like Damascenone. We have yet to reconfirm this ourselves.]

24 year Jamaica rum with fraction #5 full of rum oil. This was fractioned via birectifier.

24 year Jamaica rum with fraction #5 full of rum oil. This was fractioned via birectifier.

[We have since matched the levels of rum oil in this rum in our own experimental rums.]

Rafael Arroyo made incredible contributions to rum production, but most of his works were lost and inaccessible until recently. In terms of Grand Arôme rums, Arroyo reformatted them from non-palatable concentrates to stand alone spirits we could call “suave” to borrow a term he liked to use. Arroyo’s work is important because more than any other, he teaches us how to begin from scratch rather than only continuing and maintaining an established process.

Rafael Arroyo made incredible contributions to rum production, but most of his works were lost and inaccessible until recently. In terms of Grand Arôme rums, Arroyo reformatted them from non-palatable concentrates to stand alone spirits we could call “suave” to borrow a term he liked to use. Arroyo’s work is important because more than any other, he teaches us how to begin from scratch rather than only continuing and maintaining an established process.

The fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces Pombe is the foundation of Grand Arôme rums and possibly what Fahrasmane meant when he cautioned that “there is the difference between the real and the so called”. The French INRA has conducted the most recent work on Pombe yeasts aimed at rum. Dunder that accumulated fatty acids may have provided the osmotic pressure to make Pombe dominant in early Jamaica rum fermentations. Early writing notes that it was not dominant at the beginning of the season, but would slowly take hold. The oenology sector is studying Pombe yeast for various uses in wine, but appears unaware that it was ever used in rum production. No current rum producer acknowledges their use, but many are suspected of using it.

The fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces Pombe is the foundation of Grand Arôme rums and possibly what Fahrasmane meant when he cautioned that “there is the difference between the real and the so called”. The French INRA has conducted the most recent work on Pombe yeasts aimed at rum. Dunder that accumulated fatty acids may have provided the osmotic pressure to make Pombe dominant in early Jamaica rum fermentations. Early writing notes that it was not dominant at the beginning of the season, but would slowly take hold. The oenology sector is studying Pombe yeast for various uses in wine, but appears unaware that it was ever used in rum production. No current rum producer acknowledges their use, but many are suspected of using it.

[We have since taken possession of a library of historic Pombe yeasts, many from rum productions, some collected 100 years ago. We have found one notable champion while testing them all and the library may help provide benchmarks for what is possible when comparing newly isolated yeasts. We have also created a great framework for experimental ferments.]

This early image comes from S.F. Ashby of the Jamaican Agricultural Experiment Station from an article titled Yeasts In Jamaican Rum Distilleries. Ashby acknowledges systematic experimentation of winery and brewery yeast in rum production. He describes a need a for congruence and notes that winery yeasts can make a rum taste “cidery”. As noted by other authors, rums need rum yeasts.

This early image comes from S.F. Ashby of the Jamaican Agricultural Experiment Station from an article titled Yeasts In Jamaican Rum Distilleries. Ashby acknowledges systematic experimentation of winery and brewery yeast in rum production. He describes a need a for congruence and notes that winery yeasts can make a rum taste “cidery”. As noted by other authors, rums need rum yeasts.

[I have achieved this same image under my microscope.]  Lots of legends come with dunder and possibly even misinformation. As proven by Arroyo, dunder is not a requisite for maintaining a pombe fermentation though it is required in practice for inducing spontaneous pombe ferments. Dunder is a source of yeast nutrients, but not as precise as modern methods of controlling YAN (yeast available nutrients). Dunder recycles various precursors of High Value Congeners. Recent investigations of Schizosaccharomyces yeasts in oenology provide leads that Pombe dunder may have unique properties relative to saccharomyces yeasts. Dunder can be infected or not, and in the case of Grand Arôme rums, most likely always was.

Lots of legends come with dunder and possibly even misinformation. As proven by Arroyo, dunder is not a requisite for maintaining a pombe fermentation though it is required in practice for inducing spontaneous pombe ferments. Dunder is a source of yeast nutrients, but not as precise as modern methods of controlling YAN (yeast available nutrients). Dunder recycles various precursors of High Value Congeners. Recent investigations of Schizosaccharomyces yeasts in oenology provide leads that Pombe dunder may have unique properties relative to saccharomyces yeasts. Dunder can be infected or not, and in the case of Grand Arôme rums, most likely always was.

Patrick Neilson, On the Manufacture of Rum in Jamaica, The Sugar Cane, Vol 3, 1871, pages 191-200. At the time, they were aware of how skimmings broke down to form carboxylic acids.

Patrick Neilson, On the Manufacture of Rum in Jamaica, The Sugar Cane, Vol 3, 1871, pages 191-200. At the time, they were aware of how skimmings broke down to form carboxylic acids.

Translated from: Parfait A., Namory M., Dubois P., 1972. Les esters éthyliques des acides gras supérieurs des rhums. Annales de Technologie Agricoles 21, 2, 199–210. It may be worth investigating whether skimmings could be added to fermentations in the form of processed cane wax. Martin and Juniper, 1970 refers to a book titled The Cuticles of Plants.

Translated from: Parfait A., Namory M., Dubois P., 1972. Les esters éthyliques des acides gras supérieurs des rhums. Annales de Technologie Agricoles 21, 2, 199–210. It may be worth investigating whether skimmings could be added to fermentations in the form of processed cane wax. Martin and Juniper, 1970 refers to a book titled The Cuticles of Plants.

Use of skimmings faded as the rum industry struggled in the beginning of the 20th century. Cane wax was processed to eventually become gramophone records, for foundry use, and for candles for the Russian Orthodox church.

Use of skimmings faded as the rum industry struggled in the beginning of the 20th century. Cane wax was processed to eventually become gramophone records, for foundry use, and for candles for the Russian Orthodox church.

[The modern Jamaica vinegar process may have started in the early 20th century after skimmings stopped being produced due to changes in sugar refining. A lot more could be said here.]

The best description of liming (and cautions to the pitfalls) comes from Circular 106, Rum Manufacture, Rafael Arroyo, 1938 (translated from Spanish). The production of High Value Congeners relies on a significant buffer which can prevent pH crash due to bacterial activity. As described by Arroyo, lime treatment has a possible role in the liberation of rum oil. Very old theories suspected that unique sugar clarification practices may have been responsible for the singular character of Batavia Arrack. The older literature also discusses the varied composition of lime. Arroyo explored this in the 1930’s, but may have dropped the emphasis later. He may have been exploring the older leads.

The best description of liming (and cautions to the pitfalls) comes from Circular 106, Rum Manufacture, Rafael Arroyo, 1938 (translated from Spanish). The production of High Value Congeners relies on a significant buffer which can prevent pH crash due to bacterial activity. As described by Arroyo, lime treatment has a possible role in the liberation of rum oil. Very old theories suspected that unique sugar clarification practices may have been responsible for the singular character of Batavia Arrack. The older literature also discusses the varied composition of lime. Arroyo explored this in the 1930’s, but may have dropped the emphasis later. He may have been exploring the older leads.

[We have learned and experience a lot here with molasses preparation based on Arroyo’s methods. We have also learned that Batavia Arrack may have also used ferments that were nearly pH neutral.]

The High Ether Process was invented by H.H. Cousins in the very beginning of the 20th century and debuted at Hampden estates. Variations of the process existed where just fatty acids from the retorts were recovered to the use of full on “muck”. The success and economy of the process may have consolidated all of the more archaic and rarer circumstance complications.

The High Ether Process was invented by H.H. Cousins in the very beginning of the 20th century and debuted at Hampden estates. Variations of the process existed where just fatty acids from the retorts were recovered to the use of full on “muck”. The success and economy of the process may have consolidated all of the more archaic and rarer circumstance complications.

[We have since tracked down two different versions of Confidential: Instruction For Making High-Ether Rum by H.H. Cousins (1906) and we can refer you to a consultant with extensive experience with the process.]

This product from Hampden may represent the perfection of the High Ether Process and is the most visible Grand Arôme rum today, however it may only be sold for non-beverage use.

This product from Hampden may represent the perfection of the High Ether Process and is the most visible Grand Arôme rum today, however it may only be sold for non-beverage use.

Patrick Neilson gives us some of the most significant time stamps on elaborate processes for rum production.

Patrick Neilson gives us some of the most significant time stamps on elaborate processes for rum production.

[We never did get any leads on rum canes.]

The most classic (who really knows if it was/is the most common) symbiotic fermentation is Clostridium Saccharobutyricum and the vector it initially reached rum fermentations was from rat eaten canes. This bacteria is most commonly associated with Jamaican rum concentrates that were exported to Europe. Arroyo gives this bacteria a lot of attention and uses it to create a full bodied, suave style rum.

The most classic (who really knows if it was/is the most common) symbiotic fermentation is Clostridium Saccharobutyricum and the vector it initially reached rum fermentations was from rat eaten canes. This bacteria is most commonly associated with Jamaican rum concentrates that were exported to Europe. Arroyo gives this bacteria a lot of attention and uses it to create a full bodied, suave style rum.

[We have isolated Arroyo’s very particular Clostridium and it has unique properties that will likely make it the most desirable to the rum industry. We even have new strategies for working with it to control risk.]

Propionibacteria are known to exist in Grand Arôme rums, but possibly not as a lone symbiotic culture. Their vector is also not entirely clear, but is noted by Fahrasmane as potentially coming from both the sugar cane stalk and molasses. Certain species are associated with the skin biome such as ACNE, but that is likely not a vector infecting rum fermentations. Propionibacteria are named for producing propionic acid, but just like Saccharobutyricum, they produce a myriad of fatty acids. Fahrasmane L., Ganou-Parfait B., 1998. Microbial flora of fermentation media. Journal of Applied Microbiology 84, 921–926.

Propionibacteria are known to exist in Grand Arôme rums, but possibly not as a lone symbiotic culture. Their vector is also not entirely clear, but is noted by Fahrasmane as potentially coming from both the sugar cane stalk and molasses. Certain species are associated with the skin biome such as ACNE, but that is likely not a vector infecting rum fermentations. Propionibacteria are named for producing propionic acid, but just like Saccharobutyricum, they produce a myriad of fatty acids. Fahrasmane L., Ganou-Parfait B., 1998. Microbial flora of fermentation media. Journal of Applied Microbiology 84, 921–926.

Pineapple disease (Ceratocystis paradoxa) is a strange black mold producing an aroma reminiscent of pineapple and it is hard to say how widely it was used. It may even explain accounts of rum fermentations that resemble carbonic maceration with whole canes tossed in. Pineapple disease may have been mostly eradicated by changes to cane field management techniques. It may re-emerge in Hawaii as plantings are being made for the artisan rum industry. Not all cane varieties respond to it the same.

Pineapple disease (Ceratocystis paradoxa) is a strange black mold producing an aroma reminiscent of pineapple and it is hard to say how widely it was used. It may even explain accounts of rum fermentations that resemble carbonic maceration with whole canes tossed in. Pineapple disease may have been mostly eradicated by changes to cane field management techniques. It may re-emerge in Hawaii as plantings are being made for the artisan rum industry. Not all cane varieties respond to it the same.

[At the conference I found a producer in Grenada who acknowledged having Pineapple disease in there fields and was excited to investigate its potential future.]

Saprochaete suaveolens as a rum fermentation complication is an idea original to Arroyo as far as I can tell, though it was previously known to the flavouring industry. Arroyo classified Saprochaete suaveolens as a mold, but it was subsequently reclassified as an alt yeast. A new generation of basic research in the flavouring industry has revealed more about the working of this yeast.

Saprochaete suaveolens as a rum fermentation complication is an idea original to Arroyo as far as I can tell, though it was previously known to the flavouring industry. Arroyo classified Saprochaete suaveolens as a mold, but it was subsequently reclassified as an alt yeast. A new generation of basic research in the flavouring industry has revealed more about the working of this yeast.

[We have since isolated and explored Suaveolens, however it is finicky. Cory is slowly becoming an expert on this category of yeasts which may be immensely valuable to the industry.]

Rumors abound in the rum lore of fruit starters being used at the beginning of fermentation [Cough! cough!]. No papers detail the process, but possibly distillers were after aroma-beneficial epiphyllic micro organisms and possibly Suaveolens specifically.

Rumors abound in the rum lore of fruit starters being used at the beginning of fermentation [Cough! cough!]. No papers detail the process, but possibly distillers were after aroma-beneficial epiphyllic micro organisms and possibly Suaveolens specifically.

The rum industry has new tools available to help it tap into the potential of fermentation complications and the pursuit of HVCs. The first image is the birectifier fractioning still which allows affordable isolation of HVCs and the second image is of yeast immobilized in alginate beads. (Full disclosure: The presenter sells the birectifier)

The rum industry has new tools available to help it tap into the potential of fermentation complications and the pursuit of HVCs. The first image is the birectifier fractioning still which allows affordable isolation of HVCs and the second image is of yeast immobilized in alginate beads. (Full disclosure: The presenter sells the birectifier)

Alginate beads are a novel way to isolate yeasts, bacteria, and molds for symbiotic fermentations. These have the potential to be purchased from yeast houses to reduce the technical burden on a distillery. They can enter the fermentation in a basket at a certain density, run a measured course following best bets, and then be removed. Pombe yeasts isolated in ICT beads are already being used in the wine industry to reduce malic acid in wine. The increased osmotolerance of immobilized yeast is acknowledged by the desert wine industry.

Alginate beads are a novel way to isolate yeasts, bacteria, and molds for symbiotic fermentations. These have the potential to be purchased from yeast houses to reduce the technical burden on a distillery. They can enter the fermentation in a basket at a certain density, run a measured course following best bets, and then be removed. Pombe yeasts isolated in ICT beads are already being used in the wine industry to reduce malic acid in wine. The increased osmotolerance of immobilized yeast is acknowledged by the desert wine industry.

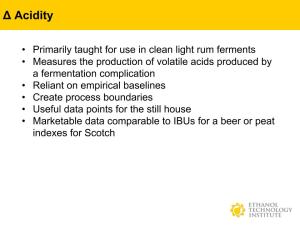

The Δ Acidity concept is primarily taught for making clean ferments for light bodied rums where any deviation is a flaw and was first written about by Michel de Miniac (translated to English). The concept can likely be repurposed to measure aroma creation in symbiotic fermentations and then arrest them, such as removing ICT beads, once certain targets are met. Δ Acidity is also a marketable concept complementary to ideas like proof of distillation (implying flavor), IBUs in brewing or PPM peat indexes for Scotch.

The Δ Acidity concept is primarily taught for making clean ferments for light bodied rums where any deviation is a flaw and was first written about by Michel de Miniac (translated to English). The concept can likely be repurposed to measure aroma creation in symbiotic fermentations and then arrest them, such as removing ICT beads, once certain targets are met. Δ Acidity is also a marketable concept complementary to ideas like proof of distillation (implying flavor), IBUs in brewing or PPM peat indexes for Scotch.

[We have recently acquired a very high end automatic titrator and will be exploring the Δ Acidity concept, but it has also taken on a unique dimension in our current work.]

The Micko distillation concept comes from Karl Micko in the early 20th century and eventually evolved into a set of protocols using the birectifier. This can be used as a tool to rapidly and broadly survey role models, competitors, and your own production to gain insights, find the patterns of quality, isolate HVCs, identify hard to reach flaws, etc. This was the central tool used by Arroyo to create suave stand alone versions of Grand Arôme rums. Arroyo used it to screen yeasts for properties like rum oil production, fermentation optimization, distillation optimization, and maturation monitoring. The individual fractions are invaluable for teaching sensory skills. The technique set may take new relevance with automation.

The Micko distillation concept comes from Karl Micko in the early 20th century and eventually evolved into a set of protocols using the birectifier. This can be used as a tool to rapidly and broadly survey role models, competitors, and your own production to gain insights, find the patterns of quality, isolate HVCs, identify hard to reach flaws, etc. This was the central tool used by Arroyo to create suave stand alone versions of Grand Arôme rums. Arroyo used it to screen yeasts for properties like rum oil production, fermentation optimization, distillation optimization, and maturation monitoring. The individual fractions are invaluable for teaching sensory skills. The technique set may take new relevance with automation.

[This has proven invaluable and we have learned to take it much further and accumulate incredible case studies to learn from. There is no better education for a distiller than studying role models with the birectifier.]

Analog and organoleptic assessment is not obsolete. It is also part of a marketing story as “proof of work” as well as “visual proofs of quality”. These tests are also important for hard to reach congeners like rum oil terpenes that cannot be titrated for. Among the only way to assess rum oil before pursuing advanced procedures like spectroscopy is organoleptically. The Germans developed the first four tests which were also used by Arroyo. The last test is a promising analog technique I have only begun exploring.

Analog and organoleptic assessment is not obsolete. It is also part of a marketing story as “proof of work” as well as “visual proofs of quality”. These tests are also important for hard to reach congeners like rum oil terpenes that cannot be titrated for. Among the only way to assess rum oil before pursuing advanced procedures like spectroscopy is organoleptically. The Germans developed the first four tests which were also used by Arroyo. The last test is a promising analog technique I have only begun exploring.

[At the conference, every large producer used GCMS but described limitations. Everything wanted to do more organoleptic analysis.]

The Grand Arôme rum tradition offers incredible opportunity to both market spirits in a new way and tap into a scientific tradition that can maximize High Value Congeners, organoleptic potential, and thus the value of rum.

The Grand Arôme rum tradition offers incredible opportunity to both market spirits in a new way and tap into a scientific tradition that can maximize High Value Congeners, organoleptic potential, and thus the value of rum.

Consumer demand has never been stronger and the fine category of spirits is seeing increased opportunity to absorb new entrants. The Grand Arôme tradition offers broad avenues of options to create marques that complement each other just as much as compete. HVCs talk, and the broad avenues to achieve them allows for inclusion. All advancement in the rum industry going forward would be wise to integrate themselves to agro tourism. Investments will have to be made, but there is a clear outlook for ROI.

Consumer demand has never been stronger and the fine category of spirits is seeing increased opportunity to absorb new entrants. The Grand Arôme tradition offers broad avenues of options to create marques that complement each other just as much as compete. HVCs talk, and the broad avenues to achieve them allows for inclusion. All advancement in the rum industry going forward would be wise to integrate themselves to agro tourism. Investments will have to be made, but there is a clear outlook for ROI.

In the last five years there has been an incredible amount of lost rum production literature recovered. Rum is turning out to be the most documented of all the spirits categories. The rarest books have been digitized and freely shared. Journals held in off site storage have been recovered at great effort and first time digitized. Works have been translated from French, Dutch, Spanish, and German into English. Popular authors are starting to use this literature to generate interest in rum as well as technical writers synthesizing the literature to produce actionable leads for production improvement.

In the last five years there has been an incredible amount of lost rum production literature recovered. Rum is turning out to be the most documented of all the spirits categories. The rarest books have been digitized and freely shared. Journals held in off site storage have been recovered at great effort and first time digitized. Works have been translated from French, Dutch, Spanish, and German into English. Popular authors are starting to use this literature to generate interest in rum as well as technical writers synthesizing the literature to produce actionable leads for production improvement.

We are acessibilizing and repopularizing lost texts, but we are not stuck in the 1940’s. We can learn cleverness and pragmatism through older works whose authors were exceptional scientists, but modern bio technology will always be the best guide through traditional practices. The old texts will always help us develop marketing arguments that can support practices and build a compelling narrative for rum.

We are acessibilizing and repopularizing lost texts, but we are not stuck in the 1940’s. We can learn cleverness and pragmatism through older works whose authors were exceptional scientists, but modern bio technology will always be the best guide through traditional practices. The old texts will always help us develop marketing arguments that can support practices and build a compelling narrative for rum.

[Since, I have finished translating Kervegant’s massive 500 page text.]

Besides comprehensive texts, one of the best solutions to education is hands on deconstruction of role models across spirits categories. As estates do more on premise, lost arts like blending with concentrates can be relearned from birectifier fractioning and the classic organoleptic tests. Performing exercises can build valuable intuition.

Besides comprehensive texts, one of the best solutions to education is hands on deconstruction of role models across spirits categories. As estates do more on premise, lost arts like blending with concentrates can be relearned from birectifier fractioning and the classic organoleptic tests. Performing exercises can build valuable intuition.

Cursory investigations into elusive congener categories like rum oil have produced strong leads that are turning up research valuable to the rum industry in other fields. There is tremendous interest in High Value Terpenes in other fields that rum may be able to benefit from.

Cursory investigations into elusive congener categories like rum oil have produced strong leads that are turning up research valuable to the rum industry in other fields. There is tremendous interest in High Value Terpenes in other fields that rum may be able to benefit from.

Interest in rum is growing, but it still has tremendous untapped potential. A Pombe renaissance may be the next leg up for rum. The concept of complications introduced here may create well diversified products that can enduringly dominate consumer interest and shelf space. Significant value can be unlocked by exploring rum’s production heritage from skimmings to rum canes. There is currently plenty of room to push organoleptic boundaries for quality by championing a focus on HVCs. Influencers are eager for new rum concepts. Anything delicious, heritage, archaic, and surrounded by passion is a driver for agro tourism. Many spirit categories have been neglecting their fine marques and have squeezed commodity products into the floor, but modern biotech can guide traditional practices to a new golden era.

Interest in rum is growing, but it still has tremendous untapped potential. A Pombe renaissance may be the next leg up for rum. The concept of complications introduced here may create well diversified products that can enduringly dominate consumer interest and shelf space. Significant value can be unlocked by exploring rum’s production heritage from skimmings to rum canes. There is currently plenty of room to push organoleptic boundaries for quality by championing a focus on HVCs. Influencers are eager for new rum concepts. Anything delicious, heritage, archaic, and surrounded by passion is a driver for agro tourism. Many spirit categories have been neglecting their fine marques and have squeezed commodity products into the floor, but modern biotech can guide traditional practices to a new golden era.

Hello,

I wanted to thank you for your work and this site which seems abysmal! I have been distilling in my cellar for 15 years and, having lived in Réunion for 4 years, I started distilling molasses the Jamaican way with live dunder. The rum thus produced without real theoretical knowledge pleased me a lot. A rum seller even told me that he had never smelled a rum like this in Reunion and called it “Jamaican”!!! I was happy. Even if after tasting he found it too “flat”. It was because of my watering down too quickly and intensely…a mistake.

But that was before. Before knowing your site. I felt like I was Alice in Wonderland. I discovered a world behind a small door. And behind this world, other worlds still.

The rules of the art would like me to select a local S. Pombe yeast because I would like to create my micro distillery, but I lack the technical means and I will probably do the simplest thing.

But I am

determined to continue working on quality. A thousand questions mainly on the preparation of molasses: should we decant it after acidification, since we cannot filter it, can we make it flocculate (fining)? But is it really necessary?

I built my reflux still, (equivalent to 4 trays). I carried out the reflux for 1 hour then double distillation type “Charentais”. Is it better or worse?

In short, I continue my exciting readings on your site by giving you thanks!

cordially

Thomas