Follow along: IG @birectifier

Kervegant Chapter XII Rhum in Food and Medicine:

Pages 316-329

CHAPTER XII

RUM IN FOOD AND MEDICINE

Physiological properties of alcohol.

Ingested at low doses, alcohol stimulates the secretion of saliva, quastric juice and pancreatic juice. However, as soon as its proportion in gastric juice reaches 2%, it slows down the action of pepsin, and stops it completely at a dose of 15%. The increase in appetite generally attributed to alcoholic drinks is due either to the excitement exerted on the organs of taste, or to the production of a general state of well-being.

In moderate doses, alcohol supports the strengths of those who have to provide strenuous physical work. In cold countries in particular and, under certain conditions, in hot countries, it is a valuable stimulant, giving the body the “coup de fouet” necessary to combat climatic influences.

[coup de fouet seems to translate to whiplash, but that doesn’t seem to appropriate…]

The question of the use of alcohol by the body has been the subject of much controversy. The work of Chauveau (1) tended to show that the substitution, with a certain quantity of carbohydrates or fats, of an isodynamic quantity of alcohol gave unfavorable results; it had the effect of a diminution of muscular power and an increase of energy expenditure in relation to the value of the work accomplished.

(1) C. R. CXXXII, 65, 110, 1901.

The more scientific experiments carried out by Atwater and Benedict (2) have shown that in normal and healthy men, moderate-doses of alcohol (1 gr / kg of weight and per day) could replace, from the point of view of the production of heat and muscular work, isodynous quantities of ternary foods. In addition, it was found that alcohol opposed the disassimilation of albuminoid materials. Other authors have since reported that it decreases muscle intoxication due to fatigue and increases the assimilability of the basal ration.

(2) An experimental inquiry regarding the nutritive value of alcohol. Washington, 1902

At high doses, especially if they are repeated daily, alcohol passes into the general circulation without being oxidized and produces toxic effects manifested by a wide variety of morbid disorders. It has an irritant action first, then degenerative on all tissues with which it is in contact: liver tissue (cirrhosis), arterial (aneurysm), renal (Bright’s disease) and especially nervous (paralysis, insanity). The schlerogenic and steatogenic processes that it causes are very similar to those observed in old age. “Alcoholism,” says Lannelongue, “is only an anticipated old age … The drinker, at 40, has the tissues of a man of 60.” Moreover by reducing the vital reactions of organs, alcohol makes it much more vulnerable to infectious agents.

“The alcoholic,” writes Dr. L. Jacquet (3), “by the daily absorption of average doses of spirits, undergoes some and usually several of these defects, which constitute, for us, the stigmata of alcoholism (dreams of nightmares, cramps, tingling, digestive disorders, cutaneous and muscular hyperaesthesia, etc.). Sooner or later, by mere exaggeration of these disorders, he will get one or other of the diseases peculiar to alcohol (paralysis, delirium tremens, insanity, etc.). Or, as a pathway, vitality diminished and fragility increased, parasitic aggression will find him defenseless and he will undergo the infection under one of its forms, tuberculosis, for example”.

(3) Presse médicale, 9 déc. 1899.

From what dose does alcohol stop being a food and a beneficial stimulant, to become a toxic? Based on the experiences of Atwater and Benedict and the interpretation given by A. Gautier (1), a man in good health could consume 1.2 to 1.4 gr. alcohol per kilogram of body weight per day. This equates to a man of 65 kg. at a dose of 91 gr. alcohol, or 214 cc. 50% brandy. Duclaux also reports as harmless the daily consumption of 1 liter of wine or the corresponding amount of brandy.

(1) Ann. Anti-ale. Oct. 1903, 93.

Other authors report significantly lower rations, ranging from 15 to 45 gr. pure alcohol. Maurel (2), for example, considers that the dose of 32.5 gr. a day is always enough for an average man and excessive for many.

(2) L’alimentation et les régimes. 3° éd. Paris, 1908.

In fact, the amount of alcohol tolerated by the body depends on many factors: dilution of alcohol (harmfulness increases with concentration), time of day (fasting or after meals), lifestyle of consumers (A man with active life and engaging in muscular work can absorb larger quantities without inconvenience), individual susceptibility etc. “The sensitivity and power of resistance to alcohol,” Gruber (3) writes, “are extraordinarily varied among men, as with other drinks. The observation shows that some men, despite daily consumption of large quantities of alcohol, can live long without being more sick or less active than others that are temperate or abstinent. From these insensibles to those sensitives, in whom tiny doses of alcohol are enough to develop real disorders, there is a whole series of degrees.”

(3) Cité par Triboulet, Mathieu et Mignot – Traité de l’alcoolismo. Paris, 1905.

Some authors attach particular importance to the impurities that accompany ethyl alcohol in eaux-de-vie and consider them more harmful than alcohol itself (Furst, Richardson, Rabuteau).

The experiments carried out by Rabuteau, Dujardin-Beaumetz and Audigé, Laborde and Magnan, Joffroy and Servaux, Baer, etc., on the comparative toxicity of the various constituents of non-alcohol have found that this amounted to higher alcohols with molecular weight (Richardson’s law). Thus, amyl alcohol is 5 times more toxic than ethyl alcohol according to Dujardin-Baumetz and Audigé, 18 times more according to Joffroy and Servaux, four times more according to Baer.

[Higher alcohols are many multiples more toxic, but they also represent a scant percentage of spirits…]

An exception, however, must be made for methyl alcohol which, despite its low molecular weight, is very harmful. This body, instead of being quickly burned like ethyl alcohol, undergoes in the body a slow oxidation process, with formation of formic acid. It is absorbed in a special way by certain nervous elements and produces serious disorders: fatty degeneration of the liver, attack of the visual centers. Blindness has been observed already, after the absorption of 8 to 20 grams of methyl alcohol.

Furfurol causes epileptic convulsions and has a paralyzing effect on the lung. According to Joffroy and Servaux, the lethal dose for the rabbit would be 0.14 grams per kilogram of animal. For a man of 70 kilos, it would be about 10 grams. Ethyl aldehyde, acrolein, nitrogenous bases are also very toxic. Ethyl acetate is much less so.

However, at the low doses usually found in eaux-de-vie, impurities appear to be, according to most hygienists, only a secondary part (1). It also seems that certain toxic substances, instead of superimposing their effects, contradict each other and annihilate each other and that the argument based on the particular harmfulness of the components therefore becomes very questionable (2).

(1) It would probably be necessary to make exception for the essences which go into the composition of some aperitifs (wormwood, bitter, vermonth, etc). These essences are very stable bodies, not easily destroyed in the body, and are for the most part very violent toxins, whose action, often convulsive or epileptic, adds to that of alcohol. For example, intoxication with absinthe has particular symptoms (epileptiform seizures in particular) that are rarely observed in alcoholic intoxication.

[I can’t believe Kervegant fell for the absinthe hype based on a few articles he read… But he’s a rum man and trashing absinthe promotes rum.]

(2) Thus, in one of his experiments, Joffroy observed that by taking a quantity of alcohol necessary to kill one-half of the rabbit and adding to it the quantity of furfurol necessary to kill another half of the rabbit, a compound effect is obtained which does not kill the rabbit.

[One of my theories is that your immune system reacts to aesthetics. Fusel oil overly salient in a sensory matrix can provoke a negative reaction, but if the same absolute quantity is better obscured in the sensory matrix because of other congeners like esters or rum oil, then the reaction is different. Your immune system may also bend around rose ketones (rum oil) in a state of relaxation which has been hypothesized by certain perfumers.]

Joffroy and Servaux (3) have found that the toxic equivalent, that is to say the quantity of toxic substance necessary to bring, when in the blood, the death of a kilogram of animal, was for various eaux-de-vie (the authors do not indicate whether it is large or small):

(3) Arch. de Médecine exp. et d’Anatomie path., sept. 1895.

“What gives alcoholic beverages, they conclude, the greater part or, to put it better, almost all of their toxicity, is ethyl alcohol, because if it is the least toxic, it exceeds them so much in quantity that it plays a preponderant role in alcoholic intoxication. ”

In a report presented to the Extra-Parliamentary Commission of 1897, in the name of the Commission of Hygiene, Duclaux expresses himself in these terms: “The substances which constitute the impurities are each a poison more active than alcohol, four- twenty times more active for example for furfurol. But, brought to the tolerable state of dilution for consumption, they fall as harmful beneath the alcohol which contains them. Thus, to absorb in a rum the amount of furfurol capable of killing by injection into the veins, a consumer should drink half a cubic meter of liquid: he would have died by alcohol long before being the consumed furfurol.”

It remains however that the action of secondary products of eaux-de-vie can be added to that of ethyl alcohol. In Martinique, for example, where the consumption of alcohol reaches a high figure, it is generally admitted that young rum, especially when it comes from cane juice (grappe blanche), fatigues less the organism than old rum, richer in impurities.

Rhum consumption.

In the early days of European colonization in the West Indies, rum was one of the main drinks of the poorer classes, the wealthy preferring the wines and spirits imported from France or Spain and made it to the islands in a considerable amount.

“In addition to the ouïcou and the grappe they produce for their family,” writes Father Labat, “the inhabitants who take care of their negroes, give them in the evening and in the morning a shot of canes eau-de-vie, especially when they have worked harder than usual, or that they suffered from the rains”.

[I think ouïcou translates to all common farm crops, but I’m not sure.]

The great consumption of rum did not seem to have had very serious consequences. “Although the frequent use of eau-de-vie and spiritus liqueurs is pernicious to health”, reads in the Taffia article of the Encyclopedia of Diderot and Alembert, “it has been noted that of all liqueurs the taffia was the least evil, and this seems to be demonstrated by the excesses of our soldiers and negroes, who resist the malignancy of the eaux-de-vie made in Europe for a shorter time.”

[Caribbean rum was known to have that thing that European rum did not and that is rum oil—rose ketones. It has been noted that people could consume more Caribbean rum. Their is various evidence that these compounds that Caribbean rum has that others do not provokes unique immune reactions to alcohol. It is the pattern behind all the most prized spirits in the world, especially Jamaica rum and Batavia Arrack.]

Rum came into the ration of soldiers and sailors. The men of the English navy received their rum in kind, until 1745, at which time Admiral Vernon had it diluted with three times its volume of water: it was the “three water rum” which was replaced in 1938 by the “two water rum”.

The royal decree of March 25, 1763, fixed at one-eighth of a pint, measured in Paris (about 115 cc), the quantity of tafia used in the composition of the daily ration of soldiers and officers coming to French colonies. The distribution of rum was subsequently suppressed and then re-established at various times. During the rainy season, the soldiers also received an additional ration of tafia (1/16 of a liter, then 3 centilitres per troop), intended to be mixed with drinking water.

Even today, rum is the “wine of the poor” in some islands of the West Indies (French West Indies and Haiti). The consumption reached in Martinique, for example, the considerable figure of 24 liters per inhabitant and per year. In the English colonies, it is much smaller (1-2 liters per inhabitant), because of the high excise duties that affect the product.

Originally, rum was consumed dry, diluted with water or variously flavored (punch). The use of grog or punch preparation has become established in Europe, where preference is for rums of molasses with an accentuated aroma. In the West Indies, on the contrary, as well as in the United States, this spirit is mainly consumed as an aperitif, in cocktails, hence preference given to light rums and, in the French colonies, to those of cane juice. It is quite rare for rum to be reserved for direct tasting, in the form of a small glass after the meal, although certain types of old rum can support, without disadvantage, the comparison with good wine spirits.

Punch and grogs.

Punch is a drink of English origin, generally consisting of a mixture of eau-de-vie with water or warm milk, sweetened and flavored with lemon and various spices. Its composition varied a lot according to the times and places: an American author (1) indicates sixty-eight different ways of preparing the punch.

(1) How to mix drinks-New-York, 1862.

The origin of the word “punch” is poorly known. Fryer who traveled to English India between 1672 and 1681, derives it from the Hindu “panch” (= five), the number of ingredients in its preparation at that time being five. A French author, who wrote the article “ponche” of the “Dictionnaire Universel” of Savary des Brulons (1759-65), writes: “This name of ponche, which is French, comes from punch, as the English write it and means “a point which penetrates”, either because this liquor is pungent and at the same time agreeable, or because it gives rise, by warming up, spikes or taunts of spirit “. More likely, the word “punch” would have originated, according to Mount (2), among seafarers and would be an abbreviation of puncheon, the barrel used for packaging rum, a term derived itself from old French ponçon, ponchon, poinçon.

(2) The Oxford English Dictionary art “punch”. Oxford, 1933.

The oldest references to punch date back to 1632. “Rum is generally consumed among planters,” writes Hughes (3), either alone or in the form of punch. According to Boullaye-Le Gouz (1653), its composition was as follows: “Bolleponge is an English word which means a drink which the English use in India, made of sugar, lemon juice, eau-de-vie, nutmeg flower and rosty biscuit. Salmon (1696) indicates a similar mode of preparation: “a kind of pleasing and pleasant punch is produced with the following proportions: pure water, brandy a quart (2 pints); pure lemon juice, 1 quart; refined sugar, 1 pound. Mix. dissolve and, if desired, add grated nutmeg.

[I think the bolle prefix either refers to bowl or bread. But these words have evolved across cultures because of how they refers to multiple things at the same time.]

(3). Amer, Physitian, 1672.

The “ponche” used in the West Indies at the end of the seventeenth century was prepared, by Pere Labat, by adding to the tafia, sugar, a little cinnamon and clove powder, nutmeg, an egg yolk and a crust of roasted bread. It was diluted with water or milk.

We read in the article “ponche” of the “Universal Dictionary” of Savary des Brulons:

“It is the favorite liquor of the English, it was invented in the Islands that this nation has in America, from where it has passed to the French islands. It is composed of two parts of eau-de-vie and one of ordinary water; cinnamon sugar, powdered cloves, roasted bread, and egg yolk are added to make it thick as broth; often, instead of water, milk is added, and it is the most esteemed; it is very nourishing and it is better for the chest.”

“The composition which M. Savary gives here in Ponche does not answer faithfully to that which the English have accustomed to make for several years, for this liquor, so esteemed by this nation, is usually made with Arac, or, in its absence, with ordinary eau-de-vie (or rum), fountain water, lemon juice with some of its peel, sugar and grated nutmeg, sometimes added to it is a small piece of roast bread…”

“The English have it very much to celebrate in the East Indies. Mr. Bernier, in his trip to the Great Mogul, Volume 2, page 334, calls it by corruption “Bouleponge”, he gives it, as I just did, the same composition, after which he adds that this drink “is the loss of body and health”; but he is wrong, for it is so in the Indies, only when one makes an excess of it, as often happens to the English. “Bouleponge” comes from the English word “Bowlpunch”, which means “Punch Bowl”, because we always use a porcelain bowl to make this drink, when we run in the company of friends, this little round cup, in which everyone drinks in turn of this liquor. Te bowl is always very large or in proportion to the number of guests.”

The Encyclopedia of Diderot and Alembert describes as follows the preparation of punch, as it was done in Europe in the second half of the eighteenth century:

“The simple punch is made with a part of rum or taffia, and three parts of lemonade composed of clear water, lemon and sugar, and a small crust of toasted bread, a little grated nutmeg and a piece of lemon peel. The punch can be made more or less strong, increasing or decreasing the dose of rum, according to taste.

“Hot punch. — To make it, in a large glazed and clean pot, put four or five parts of clear water and a part of rum or good brandy, and sugar in proportion, cinnamon at will, crushed into pieces, a little nutmeg and boil everything for five or six minutes. The pot being removed from the fire, one or two eggs must be quickly broken, and the white and yellow together added to the liquor, shake it strongly with a chocolate frother; it is still heated a little and without ceasing the movement of the frother, one pours this species of broth into large porcelain cups to drink it hot. It is a very good restorative which can be used after waking and for fatigues.”

One of the most popular punch recipes at the moment is: Infuse for 20 minutes 50 grams of excellent tea in two and a half liters of boiling water; then pour it into a bowl containing 100 grams of sugar and two lemons cut into thin slices. Then add two and a half liters of rum, in a thin stream slowly poured, so that the alcohol remains on the surface, then ignite. Mix well when the flame has gone out and keep in jugs (Bogaerts).

Duplais gives the following formulas, for the preparation of rum punch syrups:

Clarify the raw sugar and cook at 32° boiling, pass through a filter; put the syrup in a container, then add the rum, lemon essence and acid, the latter dissolved in a little water; vigorously mix, cover and lute the lid with paper strips, to avoid evaporation of the alcohol; mix again after complete cooling. Hyswen tea is prepared by making a decoction with four liters of boiling water; it is added to the boiling cooked syrup. The lemon spirit is obtained by infusing the zest of 400 fresh lemons in 60 liters of 85° alcohol for 24 hours in a bain-marie, add 25 liters of water and distil. To get a delicious punch, take some of the syrup above and add it to two parts of boiling water.

[I’m not sure why the 32° is so low. Luting is a sealing technique. Sometimes still heads are luted with a paste of flour and water to seal them. This is obviously much simpler. Hyswen is likely a green tea.]

The rum-liqueur punch is, on the contrary, intended to be consumed cold in nature:

Infuse the tea in 4 liters of boiling water; let cool and squeeze; then add rum and lemon spirit in a container, add the tea infusion, clarified sugar and acid dissolved in a glass of water; mix and color with a little caramel, if necessary; fine and filter.

A finer liquor is obtained by means of the recipe:

The tea punch is made in England, with the following ingredients:

Heat the mixture of the various constituents; add 1/2 orange and 1/2 liter of a strong infusion of tea. Serve hot (Moll-Weiss).

Another recipe for tea punché includes:

Torelli indicates the following two rum punch recipes:

Hollander Punch — In a grog glass, 2 pieces of sugar, one of rum, a teaspoon of lemon juice, a slice of orange; fill with an infusion of hot tea, stir.

This punch is also made cold, by adding, in a half full cup of cold tea infusion, a glass of rum, a spoon of sugar, 2 dashes of orange juice and crushed ice, stir and garnish with an orange slice.

Milk Punch — In a grog glass, 2 pieces of sugar, a dash of lemon juice, 2 dashes of orange juice, half a glass of curaçao liqueur, a glass of rum, a slice of orange; fill with warm milk; stir and sprinkle with nutmeg.

The iced “Milk Punch” is prepared by putting in a footed large glass a spoon of powdered sugar, a teaspoon of orange, a half-glass of curaçao liquor, a glass of rum; or fill with milk, crushed ice, then stir and garnish with orange slices.

The ordinary grog is prepared by pouring, in a glass containing hot water, rum (1/10 to 1/5 of the volume of the water); add a slice of sugar and a slice of lemon.

American grog is obtained by mixing:

We add a Mdeira glass of curaçao and serve by diluting to equal volume with boiling water (Larsen).

Torelli gives the following recipe for Rhum gorg. In a grog glass, a spoon of sugar a dash of grenadine syrup, a dash of curaçao, a glass of rum. Fill with boiling water. Stir. Garnish with a slice of lemon.

Rhum Sling, by the same author, is prepared by placing in a grog glass a spoonful of sugar, a lemon peel, a Madeira glass of rum. Fill with boiling water and sprinkle with nutmeg.

Finally the Coffee grog is obtained by mixing in a grog glass: 4 pieces of sugar, a lemon peel, a glass of rum, a cup of black coffee; warm up well with Cognac and serve flambé. [I think the Cognac is what is flambéd.]

Cocktails.

The Martiniquais punch is prepared by pouring in a glass 1/3 of cooked syrup and 2/3 of rum; mix well and add a piece of lemon peel and ice.

It is in this form that we consume almost only rum in Martinique and Guadeloupe. In this last colony, however, fruit juices are frequently added: barbadine, pomme de liane, mahogany apple, etc. The consumption of punch is usually followed by that of a large glass of fresh water. Used exclusively for the preparation of the punch is the rum of vesou, young (grappe blanche) or aged in barrels, molasses rum, because of its particular aroma giving a product of inferior quality. The lemon used is lemon peel (Citrus aurantifolia) more fragrant and juicier than the lemon or big lemon (Citrus limon), used in Europe. It often happens that one dispenses to add the zest of lemon, especially when the punch is prepared with old rum.

[This a tricky paragraph. The one sentence has strange logic and its not clear cut what rums are in and what are out for a punch. Was only molasses out or also barrel aged or grappe blanche? It is atleast clear Kervegant is suspicious of old rhums and citrus peels.]

A. Torelli (1), bartender at the “Winter Palace” in Nice, gives a series of cocktails recipes, based on rum. We reproduce some of them below.

(1) Neuf cents recettes de coktails. Paris, 1927.

Rhum Cobbler — In a goblet with ice, a spoonful of grenadine syrup, a spoonful of curaçao, a madeira glass of rum. Stir, serve in a crystal goblet, add a dash of soda water, garnish with seasoned fruit, sprinkle with sugar. Straws.

Rhum cocktail — In a shaker with crushed ice, a teaspoon of grenadine syrup, a teaspoon of curaçao, a glass of rum. Shake, pass in a cocktail glass (that is to say pour into this glass through the colander) with a sugared rim; garnish with a squeezed lemon zest.

Rhum Daisy — In a shaker, with ice, a tea spoon of orgeat syrup, the juice of half a lemon, a madeira glass rum. Shake, pass into a Bordeaux glass, finish with a dash of Seltzer water.

Rhum Fix — In a crystal goblet, the juice of half a lemon, a madeira glass of rum. Shake, fill with soda. Stir garnish with chopped fruit and a straw.

Rhum Fizz — In a shaker, with crushed ice, 2 teaspoons of powdered sugar, the juice of a lemon, a dash of egg white, a madeira glass of rum. Shake, pass in a medium sized cup, Finish with a dash of soda water, a slice of lemon and straw.

Rhum Flip. — In a shaker with crushed ice, 2 teaspoons of sugar, a teaspoon of anisette, an egg yolk, a madeira glass of rum. Shake, pass in a flip glass. Sprinkle with nutmeg and serve with straws.

Another rum flip recipe given by Blanchon, consists in heating half a glass of beer, pale preferably; mix the yolk of a chilled egg with a small glass of good rum, sprinkle with grated nutmeg and ginger root, beat well and heat slowly. Then mix by pouring into a glass and serve when the foam has formed.

Rhum Julep. — In a cup, 3 mint leaves crushed, with 2 tablespoons caster sugar and a little water. Add a madeira glass of rum, crushed ice, stir, pass in a crystal goblet. Slices of orange, fruits, mint leaves and straws.

Rhum Punch. — In a shaker with crushed ice, a spoon of sugar. Dissolve with a little water; add 2 dashes of lemon or orange juice, a dash of curaçao, a madeira glass of rum. Fill with water. Pass in a wine glass. Garnish with a slice of lemon, cut fruit. Sprinkle with nutmeg. Straws.

Rhum Sangarée, — In a Bordeaux glass, a teaspoon of sugar, dissolve with a little Seltzer water, a piece of ice. Fill with a madeira glass of rum, stir and sprinkle with nutmeg.

Rhum Scaffa. — In a small flute glass, pour gently without mixing half a shot of Benedictine, half a glass of rum and add two drops of angustura.

Rhum Smash. — In a gobelet, a spoon of sugar, dissolve with a little water, two pressed fresh mint leaves, a glass of rum: fill with crushed ice, garnish with cut fruit, a mint leaf in the middle and straws.

Rhum Sours. — In a golebet with ice, a spoon of sugar syrup, a spoonful of lemon juice, a madeira glass of rum: fill with soda water. Stir, garnish with cut fruit. Straws.

Rhum Spider. — In a large crystal goblet, two dashes of angustura. a dash lemon juice, a glass of rum, a piece of ice: fill with ginger ale. Straws.

Rhum Toddy. — In a footed glass, a spoon of sugar, three dashes of angustera, a glass of rum; fill with ice water, stir, serve with straws. This drink is also served hot, replacing the ice water with boiling water.

Bicycle Punch. — In a tall glass, a few pieces of ice, a spoon of sugar, the juice of half a lemon, a spoonful of lemon syrup, a teaspoon of curaçao, a glass of rum; fill with seltzer water, stir, garnish with a slice of orange and straws.

Boston Punch. — In a big goblet, a spoon of sugar; dissolve with a little water; add a glass of lemon juice, as much rum, as much cognac: fill with ice stir, pass to another cup containing slices of orange and lemon, sliced seasonal fruits, straws.

Fancy Rhum cocktail. — In a shaker with crushed ice, a teaspoon of gum syrup, as much curaçao, a dash of angustura, a glass of rum; shake and pass in a cocktail glass with frosted edges, a zest of lemon.

Martinican cocktail.— In a shaker with crushed ice, three dashes of angustura, three dashes of curaçao, half a glass of Italian vermouth Martini Rossi, as much rum from Martinique. Shake, put in a cocktail glass, garnish with a lemon zest and short straws.

St. James Cocktail.— In a shaker with crushed ice, a spoon of sugar syrup, three dashes of curaçao, as much St. James rum. Shake, pass in a cocktail glass, garnish with a zest of lemon. Straws.

Santa Cruz Crusta. — In a shaker with crushed ice, a spoon of grenadine syrup, a teaspoon of lemon juice, two dashes of angustura, three dashes of maraschino, a glass of Santa-Cruz rum. Shake and pass in a Bordeaux glass prepared in advance as follows. Take a lemon of sufficient size to garnish the inside of the glass, remove the peel with a knife without tearing it and place it in the glass after rubbing a piece of lemon on the edge and soaking it in powdered sugar to make a frosted rim; put a brandy macerated cherry at the bottom of the glass.

Santa Cruz Punch. — In a goblet with ice, a spoonful of sugar syrup, a dash of angustura, two dashes of noyau, two dashes of curaçao, a madeira glass of Santa Cruz rum. Fill with water, garnish with slices of orange, lemon, cut fruit, straws.

Touch-Me-Not. — In a shaker with crushed ice, a teaspoon of curaçao, as much cassis, a glass of rum, a teaspoon of lemon juice, a dash of gum syrup. Shake, pass into a bordeaux glass, with the sugared rim. Straws.

Grossman gives the following cocktail recipes, among those most used in the United States:

Planter’s punch.

Dissolve the sugar in the lemon juice, then add the rum and crushed ice, and shake well. Pour into a 10-ounce cup, half-filled with finely crushed ice. Garnish with a maraschino cherry, a piece of fresh pineapple, half a slice of orange and a sprig of mint. Serve with a straw.

Zombie.

Shake well and pour into a 14-ounce Zombie cup, filled 1/4 full with ice. Garnish with a slice of orange and several sprigs of mint. Serve with a straw.

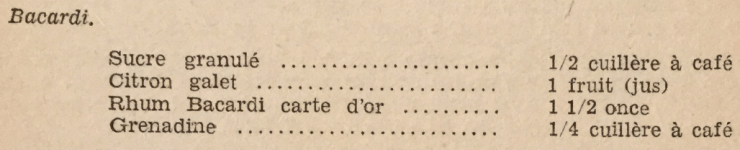

Bacardi.

First shake the lemon juice, sugar and grenadine until cool. Then introduce the rum and shake until the shaker frosts. Pass and serve.

Présidente.

Add ice, shake well and pass. [Beginning to think I should translate pass to strain.]

Rum toddy.

Fill a cup with boiling water. Place a small piece of cinnamon, a slice of large citron (lemon) garnished with 4 cloves and a thin slice of lemon peel. Stir lightly and serve with a spoon. Place a small cup of hot water next to it.

Fish house punch.

Dissolve sugar in a punch bowl. After dissolution, add the lemon juice, then the other ingredients. Introduce a piece of ice and leave the mixture to itself for about 2 hours, stirring occasionally.

Use of rum in liquoristry, pastry, etc …

Preparation of liqueurs.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the liqueurs of the islands, which came mostly from Barbados, Martinique and Guadeloupe, had a great reputation in Europe, due to the finesse of their perfume and the sweetness of their taste. The widow Amphoux-Chassevent, a native of Marseilles and who settled in 1769 in St-Pierre, Martinique, where she died in 1812, had acquired a universal reputation for her products, which were sold under the name of “liqueur de la Vve Amphoux “. Later those of Grandmaison, Fort Royal (Fort-de-France), were also highly valued (Duplais).

The liquors of the islands bore the picturesque names of: balm divin, balm humain, eau des Barbades, crême de sapotille and crême de noyau de la Martinique, crême d’ananas, cacao oil, cinnamon oil, rum oil, ginger oil, clove oil, etc.

Originally, they were made with tafia or with rum, but later these spirits were replaced by trois-six imported from Europe. We refer, for the preparation of these liqueurs, to the special works, and particularly to that of Duplais (1). We will only mention the recipe of Shrub, the best known probably rum liqueurs. [SOS I don’t understand his usage of trois-six so I left it untranslated.]

(1) Traité d ela fabrication des liqueurs. 7° éd. refondue par Arpin et Portier. Paris, 1900.

This product can be prepared as follows. To 4 liters of rum, add 1/2 liter of orange juice, 1/2 liter of lemon juice, zest of 2 oranges and 1 lemon. Let it digest cold for 24 hours, filter and sweeten with a syrup obtained by dissolving 1.5 kg. of sugar in 2 liters 1/2 of water.

Another formula is to pour in 34 gallons (154 liters) of rum at 57°, 2 ounces (56 gr.) of orange essential oil and as much lemon essential oil dissolved in a quarter (1.13 l. ) of eau-de-vie, as well as 300 pounds of sugar dissolved in 24 gallons of water. Mix well and add enough orange juice or tartaric acid solution to obtain a pleasant palatability. After agitating for a while, add 20 gallons of water to bring the volume to 100 gallons and continue stirring for half an hour. After a fortnight, the liquor, which has become clear, can be bottled (Encyclopaedia Britannica).

[What is notable about this recipe is that it is concerned about its acidity. It also does not mention anything like percentages of grand arôme rums or spices.]

Mackensie (2) gives a more complicated recipe. “Take,” he says, “8 ounces of citric acid, 16 pints of wine, 6 liters of honey, 2 pints of orange blossom water, 40 pints of very good rum, 20 of water. First dissolve citric acid in water; mix the wine and the orange blossom water together and finally mix everything, and in a week or ten days, it will be good to drink and with a very delicate perfume”.

(2) Manuel du chimiste manufacturier. Paris, 1824.

The shrub is now very simply prepared in the French West Indies, macerating for several weeks orange peel in rum of vesou (grappe blanche) and adding to the filtered liquid a sugar syrup.

Today, the liquor industry has almost disappeared in the West Indies and is mostly limited to the manufacture of some products (crême de cocoa, shrub, etc.) for family consumption.

Rum is also very common in the composition of sauces for the improvement of eaux-de-vie. Thus, to increase the aroma and taste of Armagnac brandy, we sometimes add 2 l. of rum per hl. of spirits.

The eaux-de-vie of Cognac are given a character of vétusté by means of the following “sauce”:

The mixture is poured into a hl. of eau-de-vie reduced to the proper degree, and after stirring, finish by whisking vigorously for 5 minutes.

Another formula is to macerate for a month in a liter of old rum: 2 gr. of iris powder from Florence, the zest of two small oranges and 5 gr. vanilla crushed with 50 gr. sugar. At the same time, an infusion is prepared with 15 gr. green tea, 15 gr. of linden flowers and 1 liter of boiling water. After filtration, the two liquors are combined and the mixture is added to the eau-de-vie.

Confectionery, pastry.

Confectioners use rum to flavor melting sweets, as well as candy-liqueurs, whose chocolate carapace envelops a small amount of good rum. These are sometimes presented in the form of small bottles wrapped in tin paper.

The pastry chefs use rum in many specialties, among which the place of honor is occupied by the “baba”, cake made with a leavened dough, mixed with raisins, and soaked with a rum syrup after cooking.

For the office, rum also has various uses. We can particularly note:

—rum sorbet, which is obtained by adding to the ice cream maker a vanilla syrup combined with good rum;

—rum mousse, consisting of yolk and egg white, sugar syrup, whipped vanilla cream and rum;

—rum jelly, obtained by flavoring a jelly of apples with rum, colored with a hint of caramel;

—biscuit with punch, whose preparation requires sugar, eggs, melted butter, flour and starch, all washed down with rum and flavored with lemon zest. After cooking, the biscuit is covered with an apricot marmalade and a rum ice cream. Serve with a whipped cream;

—rum pineapple compote: the fruit is cut into slices, sprinkled with sugar, which melts while giving a syrup which is mixed with rum to water the slices;

—rum cream, made of gelatin, starch, sugar and eggs, perfumed with a mixture of rum and apricot marmalade (Jourdan) (1).

(1) Les parfums de France XI, 170, 1933.

Bay rum.

Bay rum is widely used in the West Indian pharmacopoeia, in the form of refreshing applications, to fight migraine headaches and for the treatment of skin conditions in general (rashes, mosquito bites, etc.). It is also used in perfumery, especially for the preparation of hair lotions, and in soap for the manufacture of a special refreshing soap, very popular in Germany.

The product is generally obtained by mixing with rum the essence of bay (bay oil), in the proportion of 1 l. to about 250 liters of rum at 50° G.L. A little calcined magnesia is added to give a lighter, yellow-colored liquid. Sometimes other ingredients are added in small quantities (essence of Pimenta officinalis, clove, orange, etc.). In the past, Bay Rum was often prepared by direct distillation of leaves of Indian wood, which macerat for a variable time in rum (400 pounds of green leaves or 200 pounds of dry leaves per 15 gallons of Demerara rum).

Bay essence is obtained by steam distillation of green or dry leaves, wood of India (Pimenta aeris Kostel). To facilitate the release of essential oils, water containing salt is often used, or a mixture of 1/3 of sea water and 2/3 of fresh water. The yield of oil is 1.0 to 1.4% of green leaves.

The main production center of the bay rum is St-Thoms (American virgin islands), but it is also manufactured in several other islands of the Caribbean (Martinique, Guadeloupe, Dominica, St. Lucia, etc.).

Rum in therapeutics

The therapy with alcoholic beverages has sometimes been enthusiastically promoted, sometimes neglected and regarded as harmful.

The alchemists in the Middle Ages considered eau-de-vie as the universal panacea, the pre-emptive par excellence against all diseases. Arnaud de Villeneuve (1), for example, writes: “The eau-de-vie gaurds the man of venom; if he drinks, he has good luck; it purges the chest and cools the stomach; it reinforces all the animal virtues especially the memory collyrisée in the eye, it gaurds against the diseases of youth, when they are new, etc … Finally, this brandy is a water of immortality, since it prolongs the days, dissipates the sinful humours, revives the heart and maintains the youth”.

(1) De conservanda juventute. 1309.

At the opposite extreme, the naturist authors had no strong enough words to condemn the spirits: “They are good,” says Cheyne, (2) “only as violent means that are used to to blow up a house in a universal fire, in order to save some palace, that is, life itself, when it is in urgent danger. Never has the Author of Nature destined them to serve as ordinary food or drink to an animal body. Scarcely do they deserve a place in the shop of Apothecaries, having destroyed more men than did the powder with a canon.”

(2) Méthode naturelle de guérir, 1742.

With regard to rum especially, the first physicians who practiced in the colonies, recommended this spirit, taken in moderate doses, as a preventive of tropical diseases.

Dr. Dazille (3), royal doctor in Santo Domingo and former surgeon major of the Cayenne Troops, writes:

(3) Observations sus les maladies das Negres, leurs causes, leur traitement et les moyens de les prévenir, Paris, 1776.

“With a pint of tafia, 14 pints of water, a pint of lemon juice, lemon or bitter orange and a pound of raw sugar or brown sugar, we make a very fortifying drink, the use of which prevents many diseases,especially those to which blacks are most exposed. This mixture is aromatized with a sufficient quantity of peel of these same fruits, which serves as a corrective for acids and increases the tone of the stomach and intestines…”

“These drinks strengthen the stomach, increase the digestive forces and prevent excessive perspiration, which relaxes and weakens the solid parts to an excessive point. Most often, without a small glass of liquor, when sitting down to eat, the weakness of the stomach would not make it possible to take a quarter of the food necessary for the repair and renewal of moods. There are even colonies whose inhabitants are so tired by perspiration, that in the middle of the meal, and especially at dinner, they are in the habit of taking a second little glass of spiritous liquor, which they call the “middle shot…”.”

The author further observes that moderate spiritous drinks “increase the action of the stomach, cause it to discharge a greater quantity of digestive juices, support the forces, and oppose the alkalescence, as well as the putrefaction of moods”.

“I am,” said he, “so convinced of these truths, that when wine was refused to the Negroes in the King’s hospitals, and I was charged with all or part of the sick, I obtained the best effects by a sort of punch made with eau-de-vie or tafia destined for the bandages of the wounded, and whose preparation and distribution I have ordered to each of them, according to their condition.”

[There is something very Alan Alda about this… drinking the alcohol intended for bandages.]

“It is to be hoped that the government will take the necessary measures to bring such a liquor into the ration of the soldiers: 14 pints a day, or nearly enough, for an “ordinary” of seven men, thus preventing their diseases, and we would reduce their excessive mortality.

“The modest price can not be weighed against the huge sums of money they pay in hospitals and their continual replacements.”

Nowadays, alcohol medication, although it is less used than in the past, still finds its indication when it comes to raising patients who are in a state of profound depression (cholera, pneumonia, etc.). “Currently, in medical practice,” says Dr. Spire (1), “we only use alcohol, and especially rum, as a respiratory and antipyretic food, a diffusible stimulant indicated in affections with adynamic form, with cardiac asthenia. Precious, especially in states of depression, influenza, cholera, in anemias by hemorrhage, in affections where one must fear heart failure, broncho-pneumonia, pneumonia, etc. (2), rum enters the two preparations that every practitioner prescribes daily: potion of Todd, tea punches “.

(1) C.R. des Trav. de la Semaine des Rhums coloniaux. Paris, 1928.

(2) It should also be noted that in the Brehmer sanatorium in Gorbersdorf, which specializes in the treatment of lung diseases, feverish patients are sometimes treated with an entire bottle of cognac per day and that in the case of puerperal fever the only way to preserve the patients who are sick are often given high doses of alcohol.

The classic Todd potion contains the following ingredients:

It is very often prescribed in cases of general sluggishness and convalescence. Many doctors consider rum to have a tonic action more sensitive than wine eau-de-vie.

[Do not forget the theory that your immune system bends around rose ketones like damascenone in a state of relaxation.]

Rum has also been widely used and is still used in producing countries, either alone or in various flavors (bay rum) to mask the smell of alcohol vapors as a medicine for external use.

“Taffia is commonly used,” writes the Roman in the “Encyclopédie” of Diderot and d’Alembert, to rub wrinkled limbs, to relieve rheumatic pains. Frégate, snake, or dog-headed serpent oils are sometimes added; If you mix with raw egg yolks and a little hot cocoa balm, you make an excellent digestive cleans the wounds.”

The alcohol compresses at 70 or 80 ° have been used successfully to fight many inflammations, as well as to abort the suppurations. They have been used in inflammations of the phlebotomous necks, abdomen (appendicitis, tuberculous peritonitis, typhoid fever), vertebral column (cerebrospinal meningitis), skin (phlegmons, boils, panaris).

Finally, alcohol serves as a solvent for many drugs: alcoholates preparations and dyes.